animal cell structure and function pdf

Animal cells, the fundamental units of life, exhibit remarkable structure and function, forming tissues and organs. Discovered in 1665, cells are the basis of all animals.

These microscopic entities provide structure, enable movement, and contain DNA, absorbing vital nutrients for organismal survival and complex life processes.

Historical Discovery of Cells

Robert Hooke’s 1665 observation of plant cells, using a microscope, marked the initial discovery, though his view differed from modern understanding. Later, advancements in microscopy revealed the intricate structure of animal cells.

Early scientists recognized cells as the basic building blocks, establishing the cell theory. This theory solidified the understanding that all living organisms are composed of one or more cells, fundamentally shaping biology.

The Cell as the Basic Unit of Life

The cell, termed a “little room” in Latin, is the smallest structural and functional unit capable of performing life processes. Animal cells, like all cells, carry out essential functions like metabolism and reproduction.

From single-celled organisms to complex animals, the cell’s structure dictates its function, enabling life’s diverse processes. This foundational role underscores the cell’s importance in biology.

Cell Membrane: Structure and Function

The cell membrane provides a protective barrier with structure based on a phospholipid bilayer. It controls what enters and exits, vital for cell function.

Phospholipid Bilayer Composition

Phospholipids, the primary component, arrange themselves in a double layer with hydrophilic heads facing outwards and hydrophobic tails inwards. This bilayer creates a selectively permeable barrier.

Proteins are embedded within, facilitating transport, while cholesterol regulates fluidity. This dynamic structure is crucial for maintaining cell integrity and controlling the passage of substances, defining cell function.

Selective Permeability and Transport Mechanisms

The cell membrane’s selective permeability controls substance passage via various mechanisms. Passive transport, like diffusion and osmosis, requires no energy, while active transport utilizes energy to move molecules against gradients.

Facilitated diffusion employs proteins, and vesicles mediate endocytosis and exocytosis, ensuring efficient nutrient uptake and waste removal, vital for cell function.

Nucleus: The Control Center

The nucleus governs cellular activities, housing DNA. It’s a defining feature of eukaryotic cells, including animal cells, and contains genetic material for life processes.

Nuclear Envelope and Pores

The nuclear envelope, a double membrane, encloses the nucleus, separating its contents from the cytoplasm. This barrier is punctuated by nuclear pores, complex protein structures.

These pores regulate the transport of molecules – like RNA and proteins – both into and out of the nucleus, ensuring controlled communication and genetic material protection.

Essentially, they act as selective gateways, vital for gene expression and cellular function within the animal cell.

Chromatin and DNA Organization

Within the nucleus, DNA isn’t a tangled mess; it’s meticulously organized into chromatin. This complex comprises DNA tightly coiled around histone proteins, forming chromosomes.

Chromatin exists in varying degrees of condensation, influencing gene expression. Highly condensed regions are generally inactive, while looser regions allow for transcription.

This precise organization ensures efficient DNA replication, repair, and controlled access to genetic information within the animal cell.

Nucleolus: Ribosome Production

The nucleolus, a prominent structure within the nucleus, is the primary site of ribosome biogenesis. It’s responsible for transcribing ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and assembling rRNA with ribosomal proteins.

These components then migrate to the cytoplasm to form functional ribosomes, essential for protein synthesis. The size of the nucleolus correlates with the cell’s protein-making demands.

Essentially, the nucleolus ensures a constant supply of ribosomes for cellular function.

Cytoplasm: The Cellular Environment

Cytoplasm comprises the cytosol and organelles, providing a medium for cellular processes. It supports biochemical reactions and transports materials within the animal cell.

Cytosol Composition

Cytosol, the fluid portion of cytoplasm, is primarily water, alongside dissolved ions, small molecules, and macromolecules. It contains proteins facilitating metabolic pathways, and crucial for cellular functions.

These components include enzymes, nutrients, waste products, and respiratory gases, all suspended within this dynamic aqueous environment, essential for maintaining cell life and activity.

Organelles Suspended in Cytoplasm

Cytoplasm houses diverse organelles – mitochondria, ribosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes – each with specialized roles. These structures are suspended within the cytosol, enabling efficient cellular processes.

Organelles collaborate to synthesize proteins, generate energy, and manage waste, contributing to the cell’s overall function and maintaining internal homeostasis for survival.

Mitochondria: Powerhouse of the Cell

Mitochondria, visible with light microscopy, possess inner and outer membranes. They are crucial for ATP production via cellular respiration, fueling cellular activities.

These organelles convert nutrients into usable energy, sustaining life processes within the animal cell.

Structure of Mitochondria (Inner & Outer Membranes)

Mitochondria are characterized by a double membrane system. The smooth outer membrane encases the organelle, while the highly folded inner membrane creates cristae.

These cristae significantly increase the surface area for ATP synthesis. The space between membranes is the intermembrane space, and the inner membrane encloses the mitochondrial matrix, containing enzymes and DNA.

Detailed observation requires electron microscopy due to their small size.

ATP Production and Cellular Respiration

Mitochondria are central to ATP (adenosine triphosphate) production through cellular respiration. This process utilizes oxygen to break down nutrients, releasing energy stored in chemical bonds.

The electron transport chain, located on the inner mitochondrial membrane, drives ATP synthesis. Glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation are key stages, fueling cellular activities.

Essentially, mitochondria convert food into usable energy.

Ribosomes: Protein Synthesis

Ribosomes, essential for protein synthesis, exist freely or bound to the endoplasmic reticulum. They facilitate translation, converting genetic code into functional proteins.

These cellular structures are vital for building and repairing tissues, and carrying out cellular functions.

Free vs. Bound Ribosomes

Ribosomes demonstrate functional diversity, existing as either free-floating entities within the cytoplasm or bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Free ribosomes primarily synthesize proteins destined for use within the cytosol, while bound ribosomes create proteins for secretion or membrane integration.

This distinction reflects their specific roles in cellular protein production and transport pathways, contributing to overall cellular function.

Role in Translation

Ribosomes are central to translation, the process of converting genetic mRNA code into functional proteins. They bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) and, utilizing transfer RNA (tRNA), sequentially assemble amino acids into polypeptide chains.

This crucial step ensures accurate protein synthesis, essential for all cellular activities and maintaining life’s complex biochemical processes within the animal cell.

Endoplasmic Reticulum: Manufacturing and Transport

The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) is a network vital for protein and lipid synthesis, alongside intracellular transport. It’s a key manufacturing and distribution center.

ER exists in rough and smooth forms, each with specialized functions within the animal cell’s complex internal system.

Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (RER)

Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (RER) is characterized by ribosomes attached to its surface, giving it a “rough” appearance. These ribosomes are crucial sites for protein synthesis.

RER specifically manufactures proteins destined for secretion, insertion into membranes, or localization within organelles. It plays a vital role in folding and quality control of newly synthesized proteins, ensuring proper cellular function.

This organelle’s extensive network contributes significantly to the cell’s overall protein production capacity.

Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER)

Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER) lacks ribosomes, giving it a smooth appearance, and is involved in diverse metabolic processes. It synthesizes lipids, including phospholipids and steroids, essential for cell membrane structure.

SER also plays a crucial role in carbohydrate metabolism and detoxification of drugs and poisons, particularly in liver cells. Calcium ion storage is another key function, vital for muscle contraction and signaling.

Its versatility supports numerous cellular activities.

Golgi Apparatus: Processing and Packaging

The Golgi Apparatus modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for transport. Featuring cis and trans faces, it ensures proper cellular delivery and function.

Cis and Trans Faces

Golgi stacks possess distinct cis and trans faces, crucial for directional transport. The cis face, closest to the ER, receives vesicles containing proteins. Conversely, the trans face buds off vesicles carrying modified proteins destined for other organelles or secretion.

This polarity ensures efficient processing and packaging, maintaining cellular organization and functionality. Vesicles move through the Golgi, undergoing modifications as they progress.

Protein Modification and Sorting

The Golgi Apparatus meticulously modifies proteins received from the ER, adding carbohydrates or lipids – a process vital for their function. Sorting then occurs, directing proteins to their correct destinations within the cell or for export.

This precise modification and sorting ensures proteins are correctly targeted, maintaining cellular processes and organismal health. Vesicles package and deliver these proteins efficiently.

Lysosomes: Cellular Digestion

Lysosomes contain hydrolytic enzymes, breaking down waste materials and cellular debris through autophagy and phagocytosis, essential for cellular cleanup.

These organelles are crucial for maintaining cellular health and recycling components, ensuring optimal function within the animal cell.

Hydrolytic Enzymes

Hydrolytic enzymes within lysosomes are powerfully effective at digesting macromolecules – proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids – by adding water molecules.

These enzymes operate optimally in an acidic environment, maintained within the lysosome, and are crucial for breaking down complex molecules into simpler building blocks for reuse or elimination. This process is vital for cellular renewal and waste management.

Autophagy and Phagocytosis

Lysosomes facilitate autophagy, the self-digestion of damaged or unnecessary cellular components, recycling their materials. Phagocytosis involves engulfing external particles, like bacteria, and breaking them down within lysosomes.

Both processes are essential for cellular health, removing debris, and defending against pathogens. These mechanisms demonstrate lysosomes’ critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and immune responses.

Peroxisomes: Detoxification

Peroxisomes break down hydrogen peroxide, a toxic byproduct, into water and oxygen. They also metabolize fatty acids, contributing to cellular detoxification processes.

Hydrogen Peroxide Breakdown

Peroxisomes contain enzymes, notably catalase, that efficiently decompose hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into harmless water and oxygen. This process is crucial, as hydrogen peroxide is a damaging oxidative byproduct of many metabolic reactions within the cell.

Without this enzymatic breakdown, the accumulation of H2O2 would cause significant cellular damage, impacting vital functions and potentially leading to cell death. Therefore, peroxisomes play a key protective role.

Fatty Acid Metabolism

Peroxisomes are actively involved in the breakdown of fatty acids through a process called beta-oxidation. This metabolic pathway shortens long-chain fatty acids, which are then transported to mitochondria for further processing and energy production via cellular respiration.

This process is particularly important in specialized cells like liver and kidney cells, contributing significantly to energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism within the animal cell.

Cytoskeleton: Structural Support and Movement

Microtubules, intermediate filaments, and actin filaments comprise the cytoskeleton, providing structural support and facilitating cellular movement and internal organization.

This dynamic network is crucial for cell shape, intracellular transport, and various cellular processes within animal cells.

Microtubules

Microtubules are hollow tubes formed from tubulin proteins, crucial components of the cytoskeleton, providing structural support and facilitating intracellular transport within animal cells.

These dynamic structures are essential for cell division, forming spindle fibers that separate chromosomes during mitosis and meiosis. They also contribute to cilia and flagella movement, enabling cellular locomotion and fluid transport.

Intermediate Filaments

Intermediate filaments are rope-like structures providing tensile strength and maintaining cell shape in animal cells, more stable than microtubules or actin filaments.

Composed of various proteins like keratin, they resist mechanical stress and anchor organelles. These filaments are vital for structural integrity, particularly in cells experiencing physical strain, contributing to tissue stability.

Actin Filaments

Actin filaments, also known as microfilaments, are dynamic protein fibers crucial for cell shape, movement, and intracellular transport in animal cells.

They interact with myosin for muscle contraction and facilitate cell crawling and division. These filaments are highly adaptable, rapidly assembling and disassembling to meet cellular needs, providing structural support.

Centrioles and Centrosomes: Cell Division

Centrioles, within centrosomes, organize spindle fibers during mitosis and meiosis, ensuring accurate chromosome segregation for successful cell division in animal cells.

Role in Mitosis and Meiosis

Centrioles orchestrate mitosis and meiosis by forming the mitotic spindle, crucial for separating chromosomes. During prophase, they migrate to opposite poles, establishing the framework for chromosome alignment.

This precise organization ensures each daughter cell receives a complete set of chromosomes, maintaining genetic integrity. Proper spindle fiber formation is vital for successful cell division and organismal development.

Formation of Spindle Fibers

Spindle fibers, composed of microtubules, emanate from centrosomes during cell division. These fibers attach to chromosomes at the kinetochore, facilitating their movement and segregation.

Dynamic instability—growth and shrinkage—of microtubules drives spindle assembly and chromosome alignment. This intricate process ensures accurate distribution of genetic material to daughter cells during mitosis and meiosis.

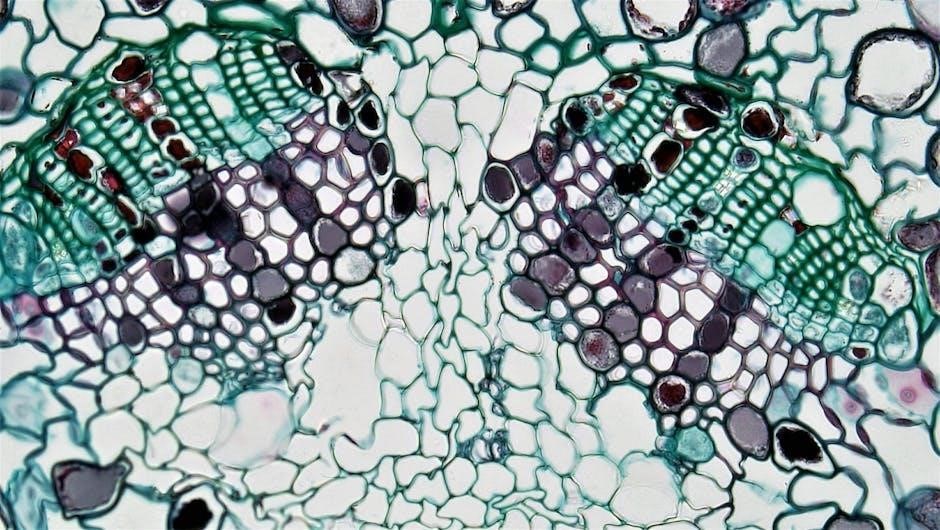

Animal Cell Diagram and Microscopy

Animal cell diagrams reveal intricate components, visualized through light and electron microscopy. These techniques showcase varying levels of detail, from basic structures to organelles.

Microscopic observation aids understanding of cellular structure and function, revealing the complexity within these fundamental life units.

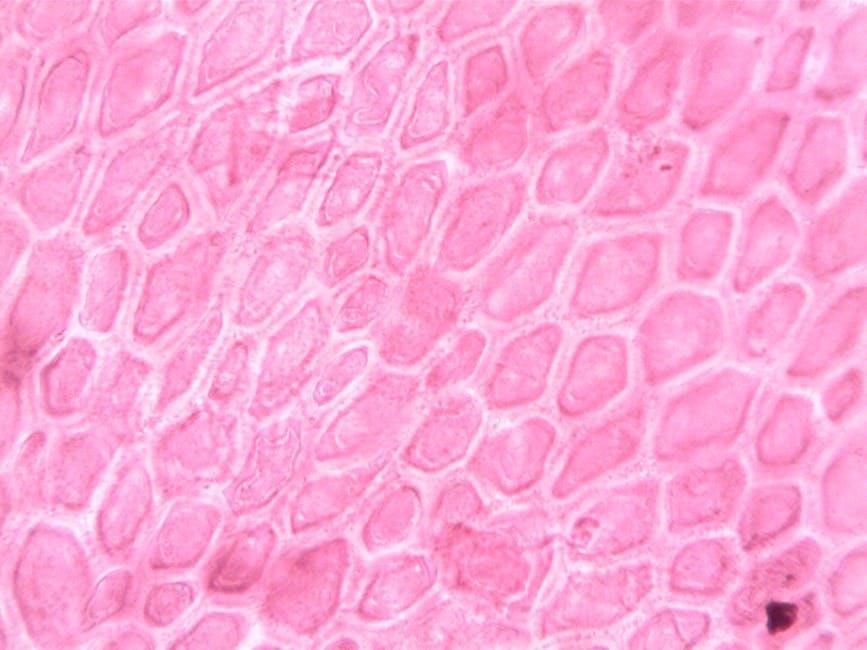

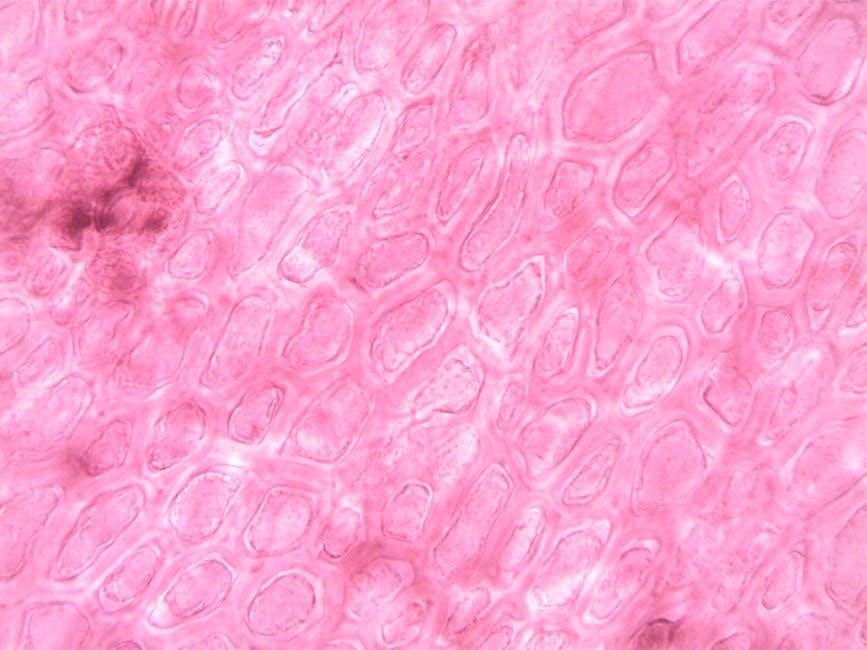

Light Microscopy vs. Electron Microscopy

Light microscopy, utilizing visible light, allows observation of basic animal cell structure, like the nucleus, but offers limited resolution. Conversely, electron microscopy, employing electron beams, provides significantly higher magnification.

This enables visualization of detailed organelles – mitochondria and ribosomes – invisible with light microscopy. While light microscopy is simpler and cheaper, electron microscopy reveals ultrastructural details crucial for understanding cellular function.

Key Features Visible Under Different Microscopes

Using light microscopy, one can readily observe the animal cell’s plasma membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm. Observing prepared cheek cell slides demonstrates these features clearly. However, detailed organelle structure remains unresolved.

Electron microscopy unveils intricate details – mitochondrial cristae, ribosome composition, and the nuclear envelope – impossible to discern with light microscopy, providing a comprehensive view of cellular architecture.

Eukaryotic Cell Characteristics

Eukaryotic cells, like animal cells, possess a defined nucleus housing DNA. This contrasts with prokaryotes, forming the basis for complex, multicellular organisms like animals and humans.

Defining Features of Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells are fundamentally characterized by a true nucleus, a membrane-bound organelle containing the cell’s genetic material – DNA. Beyond the nucleus, these cells boast other complex, membrane-bound structures called organelles, each performing specialized functions.

This internal compartmentalization allows for increased efficiency and complexity compared to prokaryotic cells. Features include a cytoskeleton for support, ribosomes for protein synthesis, and a plasma membrane enclosing the cell.

Comparison to Prokaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells, like animal cells, drastically differ from prokaryotic cells (bacteria and archaea). Prokaryotes lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, possessing a simpler structure. Their DNA resides in a nucleoid region, not a defined nucleus.

Eukaryotic cells are generally larger and more complex, enabling multicellular life, while prokaryotes are typically smaller and unicellular. Ribosomes differ in size and structure between the two cell types.

Functions of Animal Cells in Organisms

Animal cells provide essential structure and support, facilitating movement and coordinated responses to stimuli. They contain genetic material and absorb crucial nutrients.

These functions are vital for organismal survival, enabling complex processes and maintaining overall physiological balance within living systems.

Providing Structure and Support

Animal cells contribute significantly to the overall structure of organisms, forming tissues like epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous tissue. These tissues collaborate to create organs and systems.

Cellular components, including the cytoskeleton, provide internal support, maintaining cell shape and enabling tissue integrity. This foundational support is crucial for organismal form and function, ensuring stability and resilience.

Facilitating Movement and Response

Animal cells enable movement through specialized structures like actin filaments and microtubules, crucial for muscle contraction and cellular locomotion. Nerve cells transmit signals, facilitating rapid responses to stimuli.

These cellular actions allow animals to interact with their environment, coordinating behaviors like foraging, predator avoidance, and reproduction, essential for survival and adaptation within ecosystems.